Between 1752 and 1754 some 1800 fragments of ancient papyrus scrolls representing perhaps 800 original volumes were excavated from the Villa of the Papyri by Karl Weber and his team working underground. These blackened, carbonised, incredibly fragile scrolls constitute the largest surviving library from the Greco-Roman world. At Herculaneum on that fateful day in 79 CE, the heat of the pyroclastic flow, while instantly fatal to any living being in the town, was just right to carbonise these papyri and many other organic materials, instead of merely setting them alight. The subsequent mud-flow sealed everything in an oxygen-free environment, which prevented further decay.

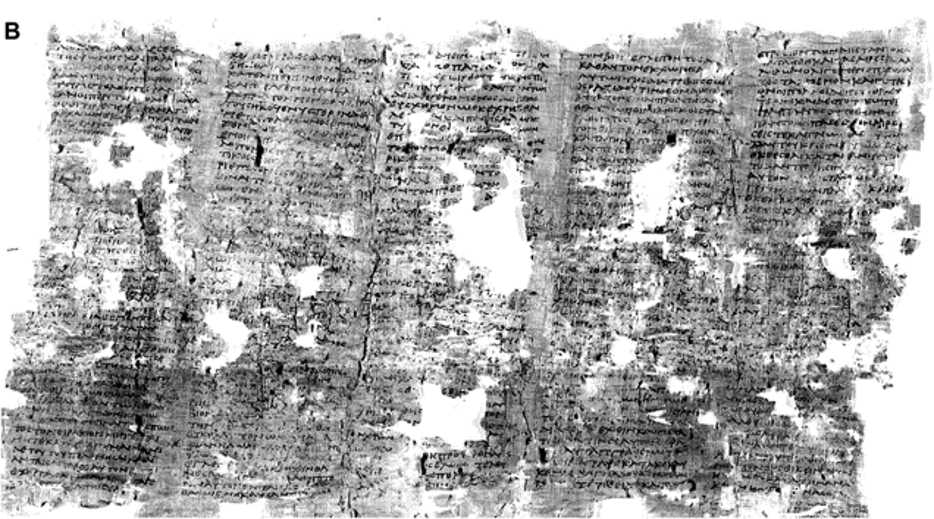

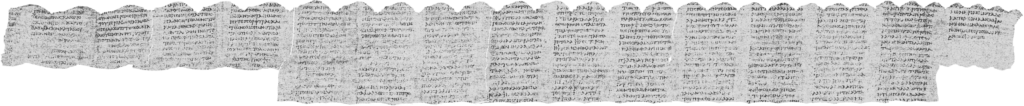

Early efforts to unroll the papyri were ruinous. Scrolls were cut in half vertically, with much loss of fabric. Exposed inner layers were legible in various degrees but typically as one layer was transcribed it was scraped off, and thus destroyed, so as to read the layer underneath. Many fragments yield up only a few letters to the naked eye.

Modern imaging techniques, such as multispectral imaging (MSI) first adapted for use with papyri by a team at Brigham Young University, have transformed our ability to read these texts. The scanner can use frequencies of light humans can’t see to distinguish the black ink from the black, carbonised background. Under optimal conditions a previously opaque sheet looks like yesterday’s newspaper. For the hundreds of fragments still rolled up, new techniques enable us to read inside them, without physical contact. For papyrus whose ink contains a metallic element (rare but not unknown at Herculaneum), the results are spectacular, as proven in a fragment of Leviticus from Ein Gedi. Work is ongoing to refine the techniques so that the charcoal-based ink used at Herculaneum can be distinguished from the papyrus, deep within the crushed and twisted scrolls. Researchers at the University of Kentucky pioneered these efforts, now augmented by teams from around the world participating in the Vesuvius Challenge. Our Newsletters regularly report on the current state of research in this area.

Through its subventions of students and scholars the Society furthers the study of the papyri at all stages, from transcription to preparation of the edited text to interpretation. The vast majority of texts deciphered to date are works of Epicurean Greek philosophy. The Villa probably belonged to the Piso family, who were patrons of Philodemus, an important representative of this school in the first century BCE and the author of most of the papyri so far identified. These works have thrown a flood of light on the literary culture of contemporary Rome and the preceding Hellenistic period. Tantalisingly, many more papyri may remain to be discovered in the Villa of the Papyri. The country residence of Roman aristocrats would contain books on all subjects, including of course many in Latin. Relatively few texts of these kinds have so far been found in the collection. Links to information on the Herculaneum papyri can be found here.

Completing the excavation of the Villa poses major problems. This must remain a long-term goal and is a matter for the Italian authorities to decide. Meanwhile the Society calls for sustainable development of the site as a whole, in itself and in relation to other historical monuments in the vicinity and the modern town of Ercolano.

When you donate to the Society you can designate papyri as your chosen project and support cutting-edge research on these utterly amazing ancient books.