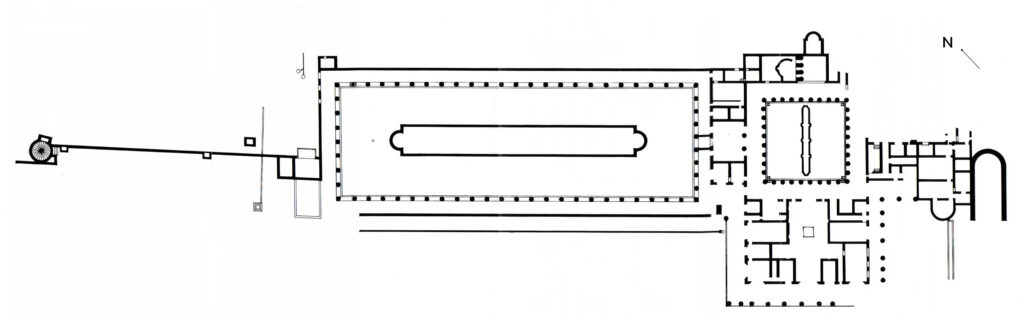

Systematic exploration of ancient Herculaneum began with the arrival of the Bourbon King of the Two Sicilies, Charles III, in 1738. In 1750, a superb polychrome mosaic floor came to light at the bottom of a well; this turned out to be the circular foundation of a belvedere, which stood at the end of a promenade leading to a huge suburban villa on the edge of ancient Herculaneum. The total frontage was over 200 metres. In addition to the traditional atrium and peristyle of a Roman house, there was a grand peristyle set at right angles to the main house with a water feature in the middle longer than a modern Olympic pool. As we know from excavation in the 1990s, there were also lower levels beneath the atrium quarter, a sizeable extension to the southeast, and a seafront pavilion. Such a building would have been affordable only by a wealthy Roman aristocrat.

The Bourbon excavation was carried out in a maze of underground tunnels constructed by the Swiss army engineer Karl Weber. The conditions were appalling: with their path lit only by smoky torches the men hacked their way through rock-hard volcanic material, battling poisonous gases and underground water. Fortunately for us, Weber had the foresight and the tenacity to map the plan of the Villa in meticulous detail, cataloguing the findspots of his discoveries. At times he incurred the wrath of his employer, who was impatient for treasures, but in due course these were delivered in abundance. The fabulous statuary and other finds are now housed in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli.

In 1752 Weber’s team began to encounter papyri. As the rolls started to be prised open, most texts proved to be by the Epicurean philosopher Philodemus of Gadara (now Um Qeis, in Jordan). Philodemus is beyond reasonable doubt the anonymous Epicurean mentioned in passing by Cicero (In Pisonem 68–72) as a writer of poetry and philosophy. We know that Philodemus had intimate connections with Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus, a very distinguished member of the Roman ruling class (and father-in-law of Julius Caesar). We also know that Philodemus had close connections with writers sympathetic to Epicureanism who spent much time in Campania. The library of the Villa contains a great many works by Philodemus—not only finished copies, but duplicate copies and drafts. It contains works by writers he criticises, and of course many books by the master Epicurus and other members of the School. It looks very much like Philodemus’ personal working library, or at least the philosophical part of it. We do not know if Piso owned a villa in this area, but our villa must have belonged to someone like him, and given the links to Philodemus he remains much the most probable owner; if not he, a member of his family.

No further excavation was conducted until the late 20th century. The southwestern part of the atrium quarter was exposed in the 1990s. To achieve this an enormous trench was sunk from the main site down to the Villa, bringing to light other buildings along the way. Since then, archaeologists have concentrated on stabilisation and conservation of the existing excavation. Many obstacles lie in the path of continuation, not least the fact that above the atrium lie the historic town hall and its garden, and various other buildings. The cost would be staggering, not only of excavating but of conserving what is excavated. Yet the Villa, and the remainder of the library it possibly contains, are of unique historical importance. The debate will continue.

Credit: Prof. Mantha Zarmakoupi, University of Pennsylvania / Parco Archeologico di Ercolano

(This page is an abridged version by the author of Robert L. Fowler’s forthcoming open access article in Manuscript and Text Cultures.)